header-includes: | \usepackage{afterpage} ...

\newpage \definecolor{titlebackground}{HTML}{313131} \pagecolor{titlebackground!20}\afterpage{\nopagecolor}

\newpage

The Robot Hacking Manual (RHM) is an introductory series about cybersecurity for robots, with an attempt to provide comprehensive case studies and step-by-step tutorials with the intent to raise awareness in the field and highlight the importance of taking a security-first1 approach. The material available here is also a personal learning attempt and it's disconnected from any particular organization. Content is provided as is and by no means I encourage or promote the unauthorized tampering of robotic systems or related technologies.

For the last fifty years, we have been witnessing the dawn of the robotics industry, but robots are not being created with security as a concern, often an indicator of a technology that still needs to mature. Security in robotics is often mistaken with safety. From industrial to consumer robots, going through professional ones, most of these machines are not resilient to security attacks. Manufacturers' concerns, as well as existing standards, focus mainly on safety. Security is not being considered as a primary relevant matter.

The integration between these two areas from a risk assessment perspective was first studied by @1673343 and later discussed by @kirschgens2018robot which resulted in a unified security and safety risk framework. Commonly, robotics safety is understood as developing protective mechanisms against accidents or malfunctions, whilst security is aimed to protect systems against risks posed by malicious actors @safetysecurity. A slightly alternative view is the one that considers safety as protecting the environment from a given robot, whereas security is about protecting the robot from a given environment. In this manual we adopt the latter and refer the reader to https://cybersecurityrobotics.net/quality-safety-security-robotics/ for a more detailed literature review that introduces the differences and correlation between safety, security and quality in robotics.

Security is not a product, but a process that needs to be continuously assessed in a periodic manner, as systems evolve and new cyber-threats are discovered. This becomes specially relevant with the increasing complexity of such systems as indicated by @bozic2017planning. Current robotic systems are of high complexity, a condition that in most cases leads to wide attack surfaces and a variety of potential attack vectors which makes difficult the use of traditional approaches.

Robotic systems and robots Both literature and practice are often vague when using the terms

robot/s and/orrobotic system/s. Sometimes these terms are used to refer to one of the robot components (e.g. the robot is the robot arm mechanics while its HMI is the teach pendant). Some other times, these terms are used to refer to the complete robot, including all its components, regardless of whether they are distributed or assembled into the same hull. Throughout this manual the latter is adopted and unless stated otherwise, the termsrobot/s and/orrobotic system/s will be used interchangeably to refer to the complete robotic system, including all its components.

\newpage

Arguably, the first installation of a cyber-physical system in a manufacturing plant was back in 1962 @historyofrobotics. The first human death caused by a robotic system is traced back to 1979 @firstkiller and the causes were safety-related according to the reports. From this point on, a series of actions involving agencies and corporations triggered to protect humans and environments from this machines, leading into safety standards.

Security however hasn't started being addressed in robotics until recently. Following after @mcclean2013preliminary early assessment, in one of the first published articles on the topic @lera2016ciberseguridad already warns about the security dangers of the Robot Operating System (ROS) @quigley2009ros. Following from this publication, the same group in Spain authored a series of articles touching into robot cybersecurity [@lera2016cybersecurity; @lera2017cybersecurity; @guerrero2017empirical; @balsa2017cybersecurity; @rodriguez2018message]. Around the same time period, @dieber2016application} led a series of publications that researched cybersecurity in robotics proposing defensive blueprints for robots built around ROS [@Dieber:2017:SRO:3165321.3165569; @dieber2017safety; @SecurecomROS; @taurer2018secure; @dieber2019security]. Their work introduced additions to the ROS APIs to support modern cryptography and security measures. Contemporary to @dieber2016application's work, @white2016sros also started delivering a series of articles [@caiazza2017security; @white2018procedurally; @white2019sros1; @caiazza2019enhancing; @white2019network; @white2019black] proposing defensive mechanisms for ROS.

A bit more than a year after that, starting in 2018, it's possible to observe how more groups start showing interest for the field and contribute. @vilches2018introducing initiated a series of security research efforts attempting to define offensive security blueprints and methodologies in robotics that led to various contributions [@vilches2018volatile; @kirschgens2018robot; @mayoral2018aztarna; @mayoral2020alurity; @mayoral2020can; @lacava2020current; @mayoral2020devsecops; @mayoral2020industrial]. Most notably, this group released publicly a framework for conducting security assessments in robotics @vilches2018introducing, a vulnerability scoring mechanism for robots @mayoral2018towardsRVSS, a robotics Capture-The-Flag environment for robotics whereto learn how to train robot cybersecurity engineers @mendia2018robotics or a robot-specific vulnerability database that third parties could use to track their threat landscape @mayoral2019introducing, among others. In 2021, @zhu2021cybersecurity published a comprehensive introduction of this emerging topic for theoreticians and practitioners working in the field to foster a sub-community in robotics and allow more contributors to become part of the robot cybersecurity effort.

\newpage

Reconnaissance is the act of gathering preliminary data or intelligence on your target. The data is gathered in order to better plan for your attack. Reconnaissance can be performed actively (meaning that you are directly touching the target) or passively (meaning that your recon is being performed through an intermediary).

Footprinting, (also known as reconnaissance) is the technique used for gathering information about digital systems and the entities they belong to.

Threat modeling is the use of abstractions to aid in thinking about risks. The output of this activity is often named as the threat model. More commonly, a threat model enumerates the potential attackers, their capabilities and resources and their intended targets. In the context of robot cybersecurity, a threat model identifies security threats that apply to the robot and/or its components (both software and hardware) while providing means to address or mitigate them in the context of a use case.

A threat model is key to a focused security defense and generally answers the following questions:

- What are you building?

- What can go wrong (from a security perspective)?

- What should you do about those things that can go wrong?

- Did you do a decent job analysing the system?

Static analysis means inspecting the code to look for faults. Static analysis is using a program (instead of a human) to inspect the code for faults.

Dynamic analysis, simply called “testing” as a rule, means executing the code while looking for errors and failures.

Formally a sub-class of dynamic testing but we separated for convenience, fuzzing or fuzz testing implies challenging the security of your robotic software in a pseudo-automated manner providing invalid or random data as inputs wherever possible and looking for anomalous behaviors.

Sanitizers are dynamic bug finding tools. Sanitizers analyze a single program excution and output a precise analysis result valid for that specific execution.

More details about sanitizers

As explained at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1806.04355.pdf:

sanitizers are similar to many well-known exploit mitigations in that both types of tools insert inlined reference monitors (IRMs) into the program to enforce a fine-grained security policy. Despite this similarity, however, exploit mitigations and sanitizers significantly differ in what they aim to achieve and how they are used

The difference is better understood by the following table (also from the paper) that compares exploit mitigations and sanitizers:

| Exploit Mitigations | Sanitizers | |

|---|---|---|

| The goal is to ... | Mitigate attacks | Find vulnerabilities |

| Used in ... | Production | Pre-release |

| Performance budget ... | Very limited | Much higher |

| Policy violations lead to ... | Program termination | Problem diagnosis |

| Violations triggered at location of bug ... | Sometimes | Always |

| Surviving benign errors is ... | Desired | Not desired |

An exploit is a piece of software, a chunk of data, or a sequence of commands that takes advantage of a bug or vulnerability to cause unintended or unanticipated behavior to occur on computer software, hardware, or something electronic (usually computerized). Exploitation is the art of taking advantage of vulnerabilities.

Robot Penetration Testing (robot pentesting or RPT) is an offensive activity that seeks to find as many robot vulnerabilities as possible to risk-assess and prioritize them. Relevant attacks are performed on the robot in order to confirm vulnerabilities. This exercise is effective at providing a thorough list of vulnerabilities, and should ideally be performed before shipping a product, and periodically after.

In a nutshell, robot penetration testing allows you to get a realistic and practical input of how vulnerable your robot is within a scope. A team of security researchers would then challenge the security of a robotic technology, find as many vulnerabilities as possible and develop exploits to take advantage of them.

See @dieber2020penetration for an example applied to ROS systems.

Robot red teaming is a targeted offensive cyber security exercise, suitable for use cases that have been already exposed to security flaws and wherein the objective is to fulfill a particular objective (attacker's goal). While robot penetration testing is much more effective at providing a thorough list of vulnerabilities and improvements to be made, a red team assessment provides a more accurate measure of a given technology’s preparedness for remaining resilient against cyber-attacks.

Overall, robot red teaming comprises a full-scope and multi-layered targeted (with specific goals) offensive attack simulation designed to measure how well your robotic technology can withstand an attack.

Robot forensics proposes a number of scientific tests and methods to obtain, preserve and document evidence from robot-related crimes. In particular, it focuses on recovering data from robotic systems to establish who committed the crime.

Review https://github.com/Cugu/awesome-forensics.

Software reverse engineering (or reversing) is the process of extracting the knowledge or design blueprints from any software. When applied to robotics, robot reversing can be understood as the process of extracting information about the design elements in a robotic system.

\newpage

Security is often defined as the state of being free from danger or threat. But what does this mean in practice? What does it imply to be free from danger? Is it the same in enterprise and industrial systems? Well, short answer: no, it's not. Several reasons but one important is that the underlying technological architectures for each one of these environments, though shares technical bits, are significantly different which leads to a different interpretation of what security (again, being free from danger and threats) requires.

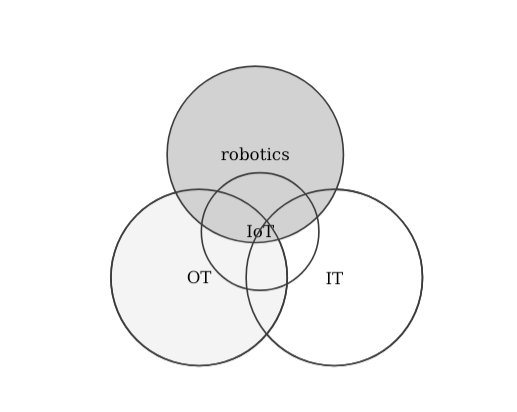

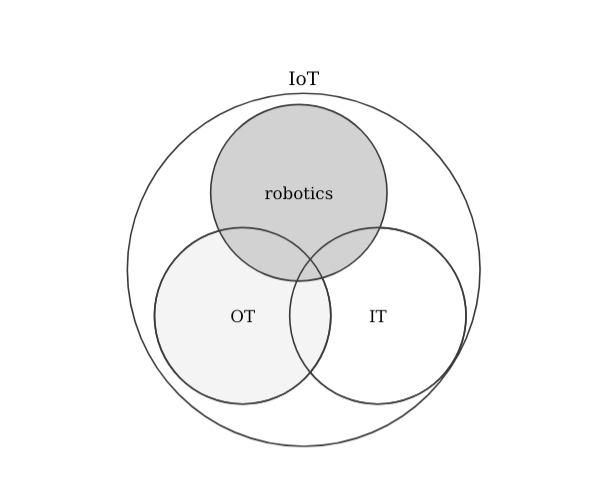

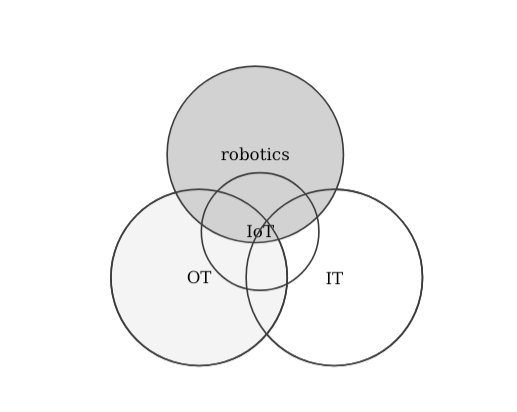

This section analyzes some of the cyber security aspects that apply in different domains including IT, OT, IoT or robotics and compares them together. Particularly, the article focuses on clarifying how robotics differs from other technology areas and how a lack of clarity is leading to leave the user heavily unprotected against cyber attacks. Ultimately, this piece argues on why cyber security in robotics will be more important than in any other technology due to its safety implications, including IT, OT or even IoT.

Over the years, additional wording has developed to specify security for different contexts. Generically, and from my readings, we commonly refer to cyber security (or cybersecurity, shortened as just "security") as the state of a given system of being free from cyber dangers or cyber threats, those digital. As pointed out, we often mix "security" associated with terms that further specify the domain of application, e.g. we often hear things such as IT security or OT security.

During the past two years, while reading, learning, attending to security conferences and participating on them, I've seen how both security practitioners and manufacturers caring about security do not clearly differentiate between IT, OT, IoT or robotics. Moreover, it's often a topic for arguments the comparison between IT and IT security. The following definitions aim to shed some light into this common topic:

- Information Technology (IT): the use of computers to store, retrieve, transmit, and manipulate data or information throughout and between organizations2.

- Operational Technology (OT): the technology that manages industrial operations by monitoring and controlling specific devices and processes within industrial workflows and operations, as opposed to administrative (IT) operations. This term is very closely related to:

- Industrial Control System (ICS): is a major segment within the OT sector that comprises those systems that are used to monitor and control the industrial processes. ICS is a general term that encompasses several types of control systems (e.g. SCADA, DCS) in industry and can be understood as a subset of OT.

- Internet of the Things (IoT): an extension of the Internet and other network connections to different sensors and devices — or "things" — affording even simple objects, such as lightbulbs, locks, and vents, a higher degree of computing and analytical capabilities. The IoT can be understood as an extension of the Internet and other network connections to different sensors and devices.

- Industrial Internet of the Things (IIoT): refers to the extension and use of the Internet of Things (IoT) in industrial sectors and applications.

- robotics: A robot is a system of systems. One that comprises sensors to perceive its environment, actuators to act on it and computation to process it all and respond coherently to its application (could be industrial, professional, etc.). Robotics is the art of system integration. An art that aims to build machines that operate autonomously.

Robotics is the art of system integration. Robots are systems of systems, devices that operate autonomously.

It's important to highlight that all the previous definitions refer to technologies. Some are domain specific (e.g. OT) while others are agnostic to the domain (e.g. robotics) but each one of them are means that serve the user for and end.

Again, IT, OT, ICS, IoT, IIoT and robotics are all technologies. As such, each one of these is subject to operate securely, that is, free from danger or threats. For each one of these technologies, though might differ from each other, one may wonder, how do I apply security?

Let's look at what literature says about the security comparison of some of these:

From 3:

Initially, ICS had little resemblance to IT systems in that ICS were isolated systems running proprietary control protocols using specialized hardware and software. Widely available, low-cost Ethernet and Internet Protocol (IP) devices are now replacing the older proprietary technologies, which increases the possibility of cybersecurity vulnerabilities and incidents. As ICS are adopting IT solutions to promote corporate connectivity and remote access capabilities, and are being designed and implemented using industry standard computers, operating systems (OS) and network protocols, they are starting to resemble IT systems. This integration supports new IT capabilities, but it provides significantly less isolation for ICS from the outside world than predecessor systems, creating a greater need to secure these systems. While security solutions have been designed to deal with these security issues in typical IT systems, special precautions must be taken when introducing these same solutions to ICS environments. In some cases, new security solutions are needed that are tailored to the ICS environment.

While Stouffer et al. 3 focus on comparing ICS and IT, a similar rationale can easily apply to OT (as a superset of ICS).

To some, the phenomenon referred to as IoT is in large part about the physical merging of many traditional OT and IT components. There are many comparisons in literature (e.g. 4 an interesting one that also touches into cloud systems, which I won't get into now) but most seem to agree that while I-o-T aims to merge both IT and OT, the security of IoT technologies requires a different skill set. In other words, the security of IoT should be treated independently to the one of IT or OT. Let's look at some representations:

What about robotics then? How does the security in robotics compare to the one in IoT or IT? Arguably, robotic systems are significantly more complex than the corresponding ones in IT, OT or even IoT setups. Shouldn't security be treated differently then as well? I definitely believe so and while much can be learned from other technologies, robotics deserves its own security treatment. Specially because I strongly believe that:

cyber security in robotics will be more important than in any other technology due to its safety implications, including IT, OT or even IoT.

Of course, I'm a roboticist so expect a decent amount of bias on this claim. Let me however further argue on this. The following table is inspired by processing and extending 3 and 5 for robotics while including other works such as 4, among others:

| Security topic | IT | OT (ICS) | I(I)oT | Robotics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antivirus | widely used, easily updated | complicated and often imposible, network detection and prevention solutions mostly | Similarly complicated, lots of technology fragmentation (different RTOSs, embedded frameworks and communication paradigms), network detection and prevention solutions exist | complicated and complex due to the technology nature, very few existing solutions (e.g. RIS), network monitoring and prevention isn't enough due to safety implications |

| Life cycle | 3-5 years | 10-20 years | 5-10 years | 10+ years |

| Awareness | Decent | Poor | Poor | None |

| Patch management | Often | Rare, requires approval from plant manufacturers | Rare, often requires permission (and/or action) from end-user | Very rare, production implications, complex set ups |

| Change Management | Regular and scheduled | Rare | Rare | Very rare, often specialized technitians |

| Evaluation of log files | Established practice | Unusual practice | Unusual practice | Non-established practice |

| Time dependency | Delays Accepted | Critical | Some delays accepted (depends of domain of application, e.g. IIoT might be more sensitive) | Critical, both inter and intra robot communications |

| Availability | Not always available, failures accepted | 24*7 | Some failures accepted (again, domain specific) | 24*7 available |

| Integrity | Failures accepted | Critical | Some failures accepted (again, domain specific) | Critical |

| Confidentiality | Critical | Relevant | Important | Important |

| Safety | Not relevant (does not apply generally) | Relevant | Not relevant (though depends of domain of application, but IoT systems are not known for their safety concerns) | Critical, autonomous systems may easily compromise safety if not operating as expected |

| Security tests | Widespread | Rare and problematic (infrastructure restrictions, etc.) | Rare | Mostly not present (first services of this kind for robotics are starting to appear) |

| Testing environment | Available | Rarely available | Rarely available | Rare and difficult to reproduce |

| Determinism requirements (refer to 6 for definitions) | Non-real-time. Responses must be consistent. High throughput is demanded. High delay and jitter may be acceptable. Less critical emergency interaction. Tightly restricted access control can be implemented to the degree necessary for security | Hard real-time. Response is time-critical. Modest throughput is acceptable. High delay and/or jitter is not acceptable. Response to human and other emergency interaction is critical. Access to ICS should be strictly controlled, but should not hamper or interfere with human-machine interaction | Often non-real-time, though some environment will require soft or firm real-time | Hard real-time requirements for safety critical applications and firm/soft real-time for other tasks |

Looking at this table and comparing the different technologies, it seems reasonable to admit that robotics receives some of the heaviest restrictions when it comes to the different security properties, certainly, much more than IoT or IT.

Still, why do robotic manufacturers focus solely on IT security?

\newpage

Insecurities in robotics are not just in the robots themselves, they are also in the whole supply chain. The tremendous growth and popularity of collaborative robots have over the past years introduced flaws in the –already complicated– supply chain, which hinders serving safe and secure robotics solutions.

Traditionally, Manufacturer, Distributor and System Integrator stakeholders were all into one single entity that served End users directly. This is the case of some of the biggest and oldest robot manufacturers including ABB or KUKA, among others.

Most recently, and specially with the advent of collaborative robots 3 and their insecurities 5, each one of these stakeholders acts independently, often with a blurred line between Distributor and Integrator. This brings additional complexity when it comes to responding to End User demands, or solving legal conflicts.

Companies like Universal Robots (UR) or Mobile Industrial Robots (MiR) represent best this fragmentation of the supply chain. When analyzed from a cybersecurity angle, one wonders: which of these approaches is more responsive and responsible when applying security mitigations? Does fragmentation difficult responsive reaction against cyber-threats? Are

Manufacturerslike Universal Robots pushing the responsibility and liabilities to theirDistributorsand the subsequentIntegratorsby fragmenting the supply chain? What are the exact legal implications of such fragmentation?

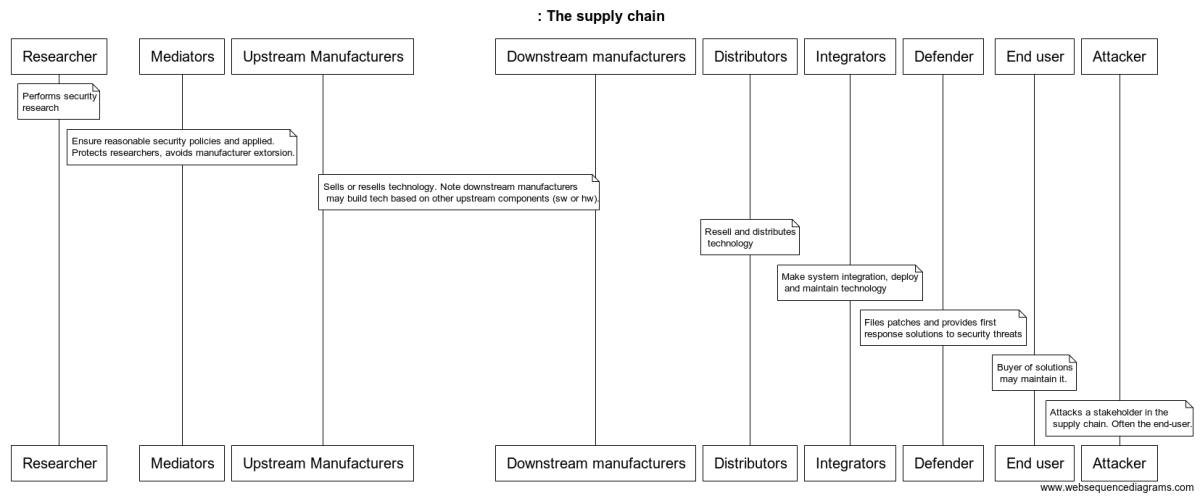

Some of the stakeholders of both the new and the old robotics supply chains are captured and defined in the figure below:

Not much to add. The diagram above is far from complete. There're indeed more players but these few allow one to already reason about the present issues that exist in the robotics supply chain.

It really isn't new. The supply chain (and GTM strategy) presented by vendors like UR or MiR (both owned by Teradyne) was actually inspired by many others, across industries, yet, it's certainly been growing in popularity over the last years in robotics. In fact, one could argue that the popularity of collaborative robots is related to this change in the supply chain, where many stakeholders contributed to the spread of these new technologies.

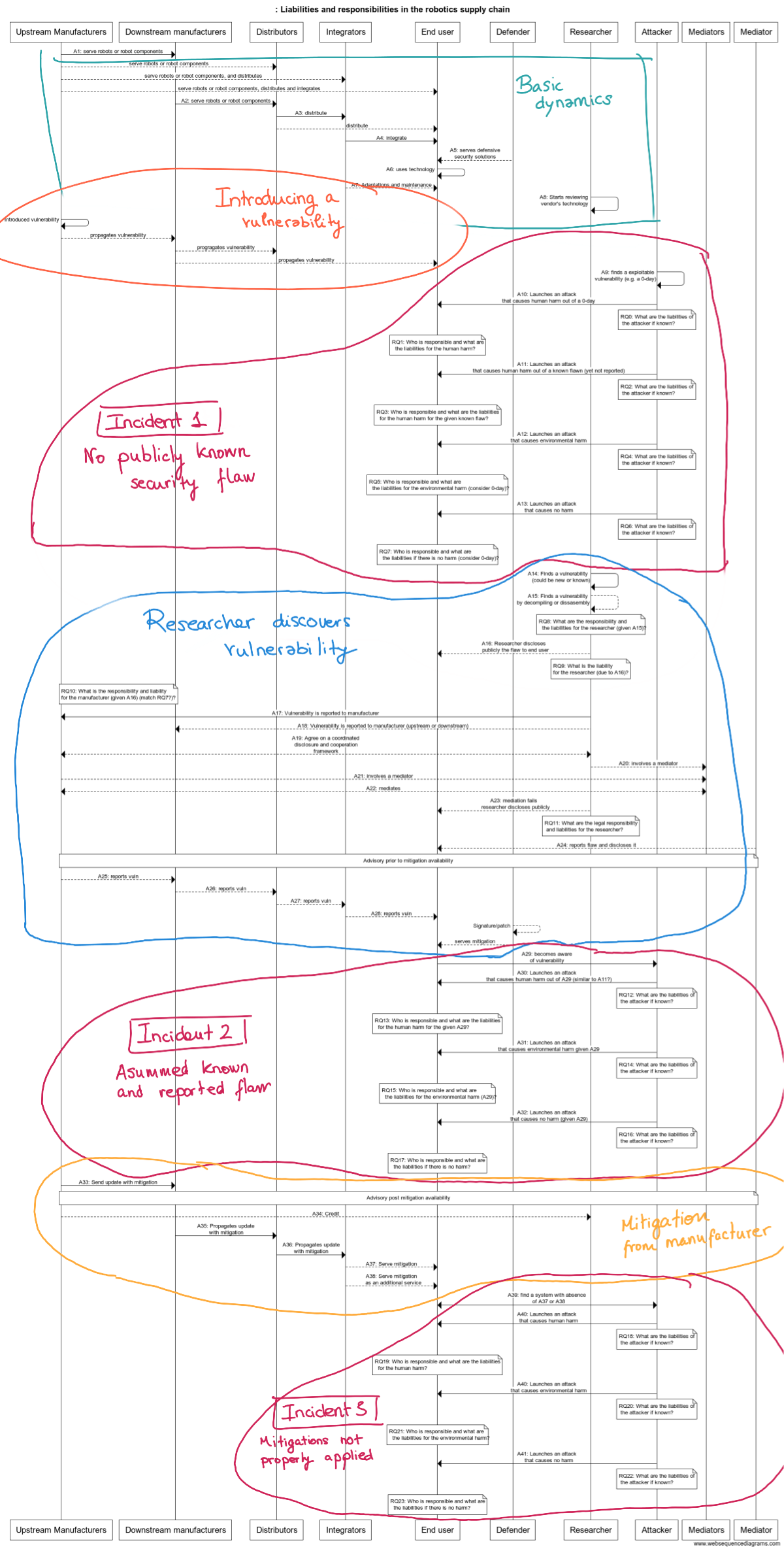

This supply chain is depicted below, where a series of security-related interactions are captured:

The diagram presents several sub-cases, each deals with scenarios that may happen when robots present cybersecurity flaws. Beyond the interactions, what's outstanding is the more than 20 legal questions related to liabilities and responsibility that came up. This, in my opinion, reflects clearly the complexity of the current supply chain in robotics, and the many compromises one needs to assume when serving, distributing, integrating, or operating a robot.

What's more scary, is that most of the stakeholders involved in the supply chain I interact with ignore their responsibilities (different reasons, from what I can see). The security angle in here is critical. Security mitigations need to be supplied all the way down to the end-user products, otherwise, it'll lead to hazards.

While I am not a laywer, my discussions with lawyers on this topic made me believe that there's lack of legal frameworks and/or clear answers in Europe for most of these questions. Morever, the lack of security awareness from many of the stakeholders involved 7 is not only compromising intermediaries (e.g. Distributors and System Integrators), but ultimately exposing end-users to risks.

Altogether, I strongly believe this 'new' supply chain and the clear lack of security awareness and reactions leads to a compromised supply chain in robotics. I'm listing below a few of the most relevant (refer to the diagram above for all of them) cybersecurity-related questions raised while building the figure above reasoning on the supply chain:

- Who is responsible (across the supply chain) and what are the liabilities if as a result of a cyber-attack there is human harm for a previously not known (or reported) flaw for a particular manufacturers's technology?8

- Who is responsible (across the supply chain) and what are the liabilities if as a result of a cyber-attack there is a human harm for a known and disclosed but not mitigated flaw for a particular manufacturers's technology?

- Who is responsible (across the supply chain) and what are the liabilities if as a result of a cyber-attack there is a human harm for a known, disclosed and mitigated flaw, yet not patched?

- What happens if the harm is environmental?

- And if there is no harm? Is there any liability for the lack of responsible behavior in the supply chain?

- What about researchers? are they allowed to freely incentivate security awareness by ethically disclosing their results? (which you'd expect when one discovers something)

- Can researchers collect insecurity evidence to demonstrate non-responsible behavior without liabilities?

I see a huge growth through fragmentation yet, still, reckon that the biggest and most successful robotics companies out there tend to integrate it all.

What's clear to me is that fragmentation of the supply chain (or the 'new' supply chain) presents clear challenges for cybersecurity. Maintaining security in a fragmented scenario is more challenging, requires more resources and a well coordinated and often distributed series of actions (which by reason is tougher).

fragmentation of the supply chain (or the 'new' supply chain) presents clear challenges from a security perspective.

Investing in robot cybersecurity by either building your own security team or relying on external support is a must.

| Title | Description |

|---|---|

| Introducing the Robot Security Framework (RSF) [@vilches2018introducing] | A methodology to perform systematic security assessments in robots proposing a checklist-like approach that reviews most relevant aspects in a robot |

| Robot hazards: from safety to security [@kirschgens2018robot] | Discussion of the current status of insecurity in robotics and the relationship between safety and security, ignored by most vendors |

| The Robot Vulnerability Scoring System (RVSS) [@vilches2018towards] | Introduction of a new assessment scoring mechanisms for the severity of vulnerabilities in robotics that builds upon previous work and specializes it for robotics |

| Robotics CTF (RCTF), a playground for robot hacking [@mendia2018robotics] | Docker-based CTF environment for robotics |

| Volatile memory forensics for the Robot Operating System [@vilches2018volatile] | General overview of forensic techniques in robotics and discussion of a robotics-specific Volatility plugin named linux_rosnode, packaged within the ros_volatility project and aimed to extract evidence from robot's volatile memory |

| aztarna, a footprinting tool for robots [@vilches2018aztarna] | Tool for robot reconnaissance with particular focus in footprinting |

| Introducing the robot vulnerability database (RVD) [@vilches2019introducing] | A database for robot-related vulnerabilities and bugs |

| Industrial robot ransomware: Akerbeltz [@mayoral2019industrial] | Ransomware for Industrial collaborative robots |

| Cybersecurity in Robotics: Challenges, Quantitative Modeling and Practice [@ROB-061] | Introduction to the robot cybersecurity field describing current challenges, quantitative modeling and practices |

| DevSecOps in Robotics [@mayoral2020devsecops] | A set of best practices designed to help roboticists implant security deep in the heart of their development and operations processes |

| alurity, a toolbox for robot cybersecurity [@mayoral2020alurity] | Alurity is a modular and composable toolbox for robot cybersecurity. It ensures that both roboticists and security researchers working on a project, have a common, consistent and easily reproducible development environment facilitating the security process and the collaboration across teams |

| Can ROS be used securely in industry? Red teaming ROS-Industrial [@mayoral2020can] | Red team ROS in an industrial environment to attempt answering the question: Can ROS be used securely for industrial use cases even though its origins didn't consider it? |

| Hacking planned obsolescense in robotics, towards security-oriented robot teardown [@mayoral2021hacking] | As robots get damaged or security compromised, their components will increasingly require updates and replacements. Contrary to the expectations, most manufacturers employ planned obsolescence practices and discourage repairs to evade competition. We introduce and advocate for robot teardown as an approach to study robot hardware architectures and fuel security research. We show how our approach helps uncovering security vulnerabilities, and provide evidence of planned obsolescence practices. |

Footnotes

-

Information technology. (2020). Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_technology. ↩

-

Stouffer, K., Falco, J., & Scarfone, K. (2011). Guide to industrial control systems (ICS) security. NIST special publication, 800(82), 16-16. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Atlam, Hany & Alenezi, Ahmed & Alshdadi, Abdulrahman & Walters, Robert & Wills, Gary. (2017). Integration of Cloud Computing with Internet of Things: Challenges and Open Issues. 10.1109/iThings-GreenCom-CPSCom-SmartData.2017.105. ↩ ↩2

-

TUViT, TÜV NORD GROUP. Whitepaper Industrial Security based on IEC 62443 ↩ ↩2

-

Gutiérrez, C. S. V., Juan, L. U. S., Ugarte, I. Z., & Vilches, V. M. (2018). Towards a distributed and real-time framework for robots: Evaluation of ROS 2.0 communications for real-time robotic applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.02595. ↩

-

Mayoral-Vilches, V. Universal Robots cobots are not secure. Cybersecurity and Robotics. ↩

-

Note this questions covers both, 0-days and known flaws that weren't previously reported. ↩